|

Perspective

- Definitions and Nomenclature

- Most Common Food Allergies

- Global Prevalance of Food Allergies

- Pathophysiology of IgE Mediated Food Allergy

- Treatment Implications

- Medical Nutrition Therapy

.png)

The European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI) defines food hypersensitivity as any adverse reaction to food which can range from minor stomach discomfort to severe anaphylaxis.(1)

The World Health Organization has developed new terminology to better describe food hypersensitivity in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11). However, it may take up to 10 years before these new terms will be implemented.(2)

Classification of Adverse Food Reactions

Adverse food reactions are categorized based on the underlying mechanisms.

- Food Allergies: Involve immunological reactions and can be immunoglobin E-mediated (IgE) , non-IGE-mediated, mixed IgE/non-IgE or cell-mediated.(3,4)

- Food Intolerances: Do not involve immunological mechanisms and can be metabolic (e.g. enzyme deficiencies), pharmacological (e.g. caffeine effect), toxic (e.g. food poisoning), or other mechanisms.(3)

Differentiating Food Allergies from Food Intolerances

The health implications of food allergies and food intolerances differ significantly, making accurate identification essential for appropriate management and treatment. Food allergies can trigger severe, potentially life-threatening reactions, while food intolerances typically result in less severe symptoms; most often gastrointestinal, although extraintestinal symptoms may present as well.(3,4)

FIGURE 1.1 Categories of food reactions(5)

.png)

Differentiating IGE-mediated Food Allergies

IgE-mediated food allergies are characterized by an immunological response that involves the production of immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies. These reactions typical occur rapidly, within minutes to hours following exposure to the allergen. Symptoms may include mild responses such as skin rash, runny nose or mild itching to more severe reactions including wheezing, coughing, vomiting, diarrhea, shortness of breath and potentially life-threatening anaphylaxis.(4)

Diagnostic tests may identify elevated levels of IgE levels aiding in confirmation of these allergic responses. Non-IgE Mediated food allergies usually involve gastrointestinal mechanisms and the reactions are usually not as rapid (can be delayed up to days) after exposure and usually not as severe.

Foods most commonly associated with food allergies in young children are cow's milk, egg and peanut, whilst in adults, peanut, tree nuts and seafood are most common.(6) The nine most common food allergies are:(7)

- Milk - an immune reaction to one or more proteins in cow's milk, such as casein and whey

- Eggs - an immune response to proteins found in egg whites, such as ovomucoid, ovalbumin, and conalbumin

- Peanuts - an immune reaction to proteins found in peanuts, such as Ara h1, Ara h2, and Ara h3

- Tree nuts - allergies include reactions to nuts such as almonds, walnuts, cashews, hazelnuts, and pistachios. The proteins responsible for these allergic reactions can vary by nut.

- Soy - an immune response to proteins found in soybeans, such as glycinin and conglycinin

- Wheat - an immune reaction to proteins found in wheat, such as gliadin and glutenin

- Fish - an immune response to proteins found in fish muscle, such as parvalbumin

- Shellfish allergies - is divided into two categories: crustacean and mollusk allergies. The allergens responsible are often tropomyosins, which are heat-stable proteins

- Sesame - an immune response to proteins found in sesame seeds, such as Ses i 1 and Ses i 2

In Australia and Mediterranean countries,

10.--Lupin, a legume made into flour.(8) The allergens are α-conglutin: A legumin-like 11S globulin, β-conglutin: A vicilin-like 7S globulin, γ-conglutin: A vicilin-like 7S globulin, δ-conglutin: A 2S albumin

The EU has also added the following common food allergens

11. Celery

12. Mollusks

13. Mustard

14. Sulfite-containing food

Fruits and vegetables can also initiate a type 1 hypersensitivity.(1)

Global Prevalance of Food Allergies

Food allergy is a significant public health concern, with its prevalence increasing notably over the past few decades, especially in Westernized regions. It currently affects 3-10% of children and up to 10% of adults.(1,3,9)

In Australia, data indicate a 10% prevalence among infants, decreasing to around 4% by 4 years of age.(10) Australia, known for high food allergy rates, reported a prevalence of 4.5% among adolescents aged 10 to 14 years.(11) (See data tables) Specifically, from the Melbourne-based HealthNuts study, peanut allergy prevalence at 12 months was 3%, egg allergy was 8.9%, and sesame allergy was 0.8%. By the four-year follow-up, these rates decreased to 1.9% for peanut allergy, 1.2% for egg allergy, and 0.4% for sesame allergy.(12)

Similarly, a study conducted in the UK found a 7.1% prevalence of food allergy in breast-fed infants at the age of 3 years.(13)

In children under 5 years old, the prevalence of challenge-proven food allergies varies across different countries. In Denmark, it is reported at 3.6%, and in Norway 6.8%.(14)

A systematic review covering European studies from 2000 to 2012 provided challenge-confirmed food allergy prevalence rates for various allergens: cow’s milk (0.6%), egg (0.2%), wheat (0.1%), soy (0.3%), peanut (0.2%), tree nuts (0.5%), fish (0.1%), and shellfish (0.1%). The review also reported higher self-reported lifetime prevalence rates: cow’s milk (6.0%), egg (2.5%), wheat (3.6%), soy (0.4%), peanut (1.3%), tree nuts (2.2%), fish (1.3%), and shellfish (1.3%).(14)

In the US, a survey indicated a self-reported food allergy prevalence of 8% among children under 18 years old, consistent with European findings.(15)

Studies on older children and adults are limited but suggest lower prevalence rates. For instance, a UK study found a 2.3% prevalence among 11-year-olds and 15-year-olds using oral food challenges (OFCs) or clinical history with positive skin prick tests.(16) A German study reported a 4.2% prevalence across all childhood ages (0–17 years)(17), while a Turkish study reported a rate of 0.15% among adolescents.(18)

These studies highlight variability in food allergy prevalence across different populations and age groups, as well as discrepancies between self-reported and confirmed diagnoses.(9)

IgE-mediated food allergies are more common in young children, with prevalence varying by region due to factors like geographic location, dietary exposure, ethnicity and age.(9,14) The increased prevalence of food allergy has been attributed to several environmental effects, including microbial exposure and allergen avoidance.

Pathophysiology of IgE-mediated Food Allergy

Food allergies can be categorized based on the role of immunoglobulin E (IgE) in their pathogenesis: IgE-mediated, non-IgE-mediated, and mixed IgE and non-IgE-mediated. Specifically, these classifications are determined by whether the underlying mechanism involves IgE-mediated (Type 1 hypersensitivity), non-IgE mediated (type III or type IV hypersensitivity), or a combination of IgE and cellular mechanisms (mixed IgE and non-IgE-mediated).(1,5,9)

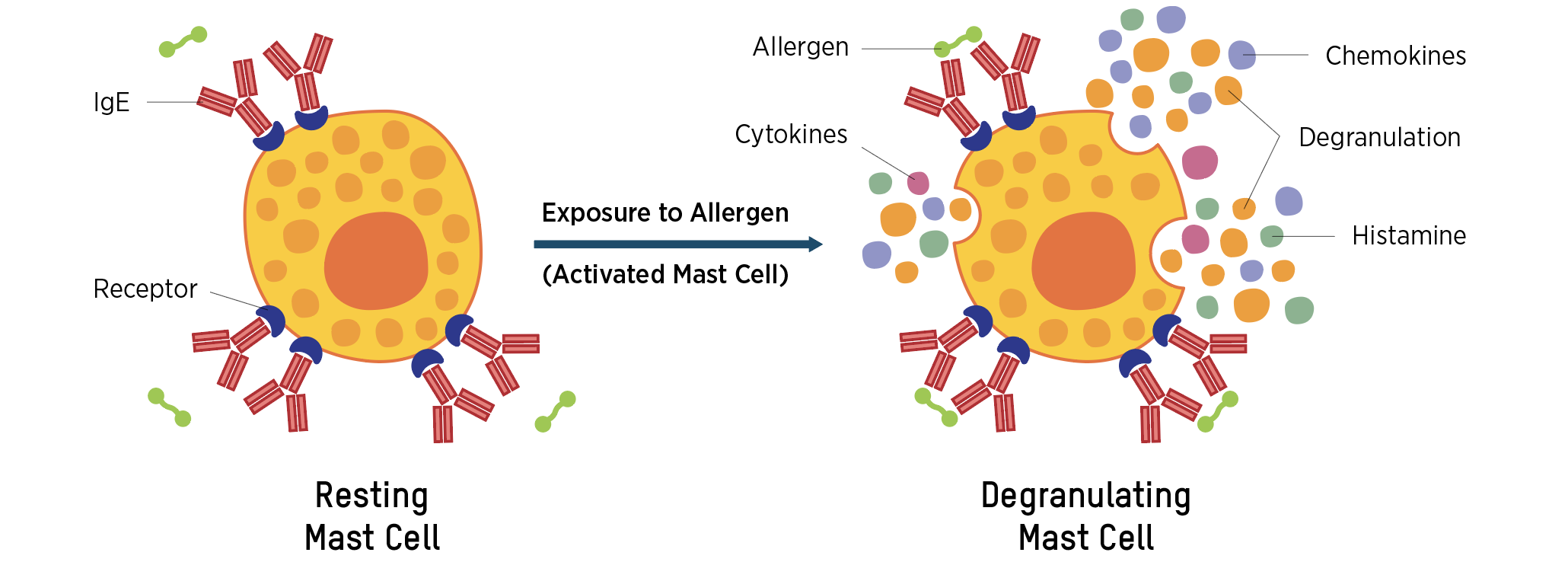

An IgE-mediated food allergy is characterized by a reproducible adverse reaction following exposure to specific antibodies known as Immunoglobulin E (IgE). This triggers an immune response with symptoms including allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, asthma, AD, acute urticaria/angioedema.(15) The pathophysiology of an IgE-mediated food allergy reaction involves two phases(1):

- Sensitization Phase: The pathophysiology of an IgE-mediated food allergy begins with the sensitization phase. Upon initial exposure to a specific food protein, this protein binds to IgE receptors on the surface of mast cells and basophils. This binding process, facilitated by the immune system, primes the individual for an allergic reaction. The body’s immune system erroneously identifies the food protein as a harmful substance, leading to the production of IgE antibodies specific to that protein.

- Allergic Response Upon Re-exposure: Upon subsequent exposure to the same food protein, the sensitized mast cells and basophils recognize the allergen and bind to it through the already present IgE antibodies. This recognition and binding triggers the release of various chemical mediators such as histamine. The release of histamine and other mediators leads to the clinical manifestations of an allergic reaction, which can range from mild symptoms such as hives and itching to severe, potentially life-threatening conditions such as anaphylaxis.(1,5)

The clinical signs and symptoms of an IgE-mediated food allergy are the direct result of these chemical mediators' actions on various tissues and organs. For example, histamine release can increase vascular permeability, leading to swelling and redness, and can stimulate nerve endings, causing itching and pain. In the gastrointestinal tract, these mediators can cause symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, while in the respiratory system, they can lead to bronchoconstriction and wheezing.

FIGURE 1.2 IgE binding to mast cells(11)

IgE-mediated food allergy occurs when allergens bind to IgE antibodies on the surface of mast cells causing release of histamine, cytokines and other inflammatory mediators.

|

Pathophogenesis/Development of IgE Mediated Food Allergy

The Dual Allergen Exposure Hypothesis

The dual allergen exposure hypothesis suggests that low-dose cutaneous exposure, particularly when the skin barrier is compromised, leads to sensitization, while oral exposure promotes tolerance. This hypothesis is supported by substantial evidence and has influenced global changes in infant feeding guidelines.(19,20)

Symptoms are evident within minutes or within 2 hours after a small amount of food containing the allergen is ingested.

TABLE 1.3 Symptoms of IgE-mediated food allergy(12,16)

| MILD-TO-MODERATE SYMPTOMS | SEVERE SYMPTOMS (ANAPHYLAXIS) | |

| Swelling of lips, face or eyes | Difficulty or noisy breathing | Wheeze or persistent cough |

| Hives or welts | Swelling of tongue | Dizziness or collapse |

| Vomiting | Difficulty talking | Pale and floppy (young children) |

| Tingling mouth | Hoarse voice or cry | Swelling/tightness in throat |

| Abdominal pain | ||

Diagnosing food allergies involves consultation with a specialist such as an allergist or immunologist. The diagnostic process involves:

- An allergy-focused medical history - a comprehensive review of the patient's allergic reactions and medical background

- The implementation of an exclusion diet - temporarily removing suspected allergens from the diet to observe symptom changes

- Skin prick tests (SPT) using allergen extracts or fresh foods

- Specific IgE to allergen extracts (sIgE)

- Specific IgE to individual allergen components (component resolved diagnosis, (CRD) test, MA, molecular allergology)

- Basophil activation test (BAT) to evaluate the activation of basophils (a type of white blood cell) when exposed to allergens - usually only in research settings

- Oral food challenge (OFC) is the gold standard for diagnosing food allergies. The patient consumes the suspected allergen under medical supervision to monitor for reactions. This test is particularly important for patients with inconclusive results from other tests.(1)

The specific diagnostic criteria and management strategies vary depending on the type of food allergy being investigated. A review of the patient's medical records is crucial for determining their stage in the diagnostic process. It is important for dietitians to understand that their therapeutic interventions may be integral to the diagnostic process and/or serve as the primary treatment.

Evolving Recommendations for Preventing Food Allergies

Dietitians must stay informed about the rapidly evolving guidelines for preventing and treating food allergies. Not long ago, the prevailing recommendation was for infants at high risk of developing food allergies to avoid foods likely to cause allergic reactions. Current strategies, particularly for specific allergens like peanuts, now advocate for early introduction protocols, which have shown to be more effective in preventing the development of allergies. This shift underscores the importance of staying current with emerging research and updated clinical guidelines. All common allergenic foods are introduced as part of a variety of solid foods in the first 12 months of life.(21)

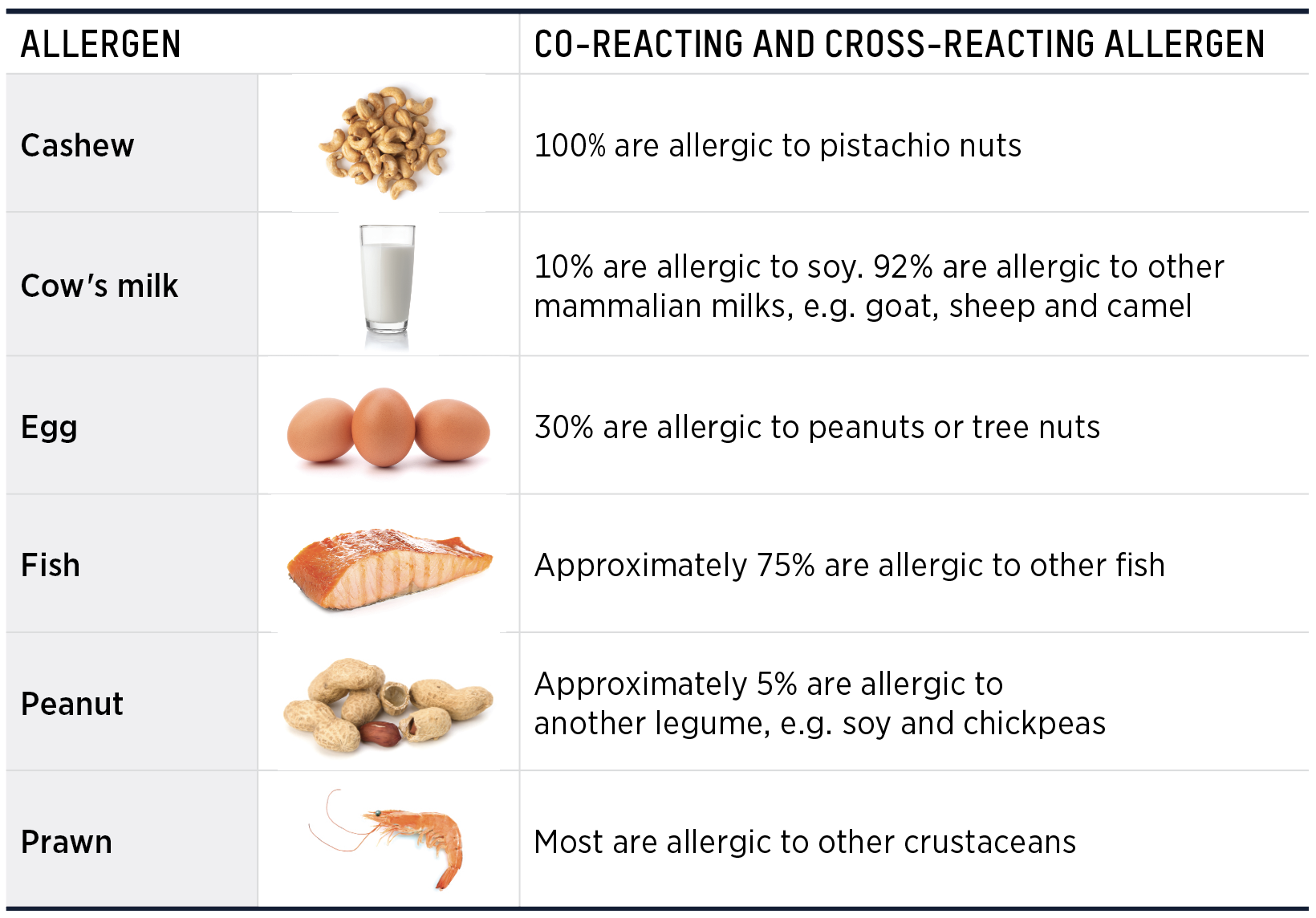

Food allergy co-reactions, also known as cross-reactivities, occur when proteins in one food share structural similarities with proteins in another, causing the immune system to react to both. Common examples include reactions between peanuts and tree nuts, or birch pollen and certain fruits (oral allergy syndrome). These co-reactions are due to the immune system recognizing similar protein epitopes in different foods. Managing these co-reactions involves strict dietary avoidance of all related allergens and thorough consultation with an allergist for accurate diagnosis and treatment plans.

TABLE 1.4 Co-reactivity and cross-reactivity(9,23)

|

Anaphylaxis Management for IgE Mediated Food Allergies

Anaphylaxis must be treated immediately with an adrenaline auto-injector and urgent transport to a hospital.(24) All individuals at risk of anaphylaxis should:

- Be familiar with the emergency procedure

- Have an Australasian Society of Clinical Allergy and Immunology (ASCIA) Action Plan or Food Allergy Research & Education (FARE) for Anaphylaxis completed by their doctor

- Carry an adrenaline auto-injector and understand its use

Death from anaphylaxis is rare. However, it is important to note a history of mild reaction does not indicate the severity of a subsequent reaction. Risk is increased by:

-

Delayed or no administration of adrenaline

-

Upright posture during anaphylaxis

-

Age: Adolescent to young adult

-

Presence of co-factors

-

Cofactors that may influence the severity of reactions are:

-

Poorly controlled asthma

-

Exercise

-

Menses

-

Acute illness

-

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS)

-

Alcohol

-

Sleep deprivation

-

Medication: B-blockers, Ace inhibitors

-

Reliance on oral antihistamine alone to treat symptoms

-

-

Growth and Nutrition

Food allergies are recognized as contributing to various health challenges affecting growth, nutrition and quality of life. The impact on growth is primarily due to dietary restrictions and associated complications. Key factors include:

- Food exclusion - essential nutrients may be omitted from the diet, particularly when common allergens like cow's milk and wheat are excluded. These foods are primary sources of essential nutrients, including calcium, vitamin D and protein.

- Unnecessary food exclusion - foods may be excluded based on suspicion rather than confirmed food allergy, leading to unnecessary dietary limitations.

- Atopic comorbidities - conditions such as eczema, which often coexist with food allergies, can affect appetite and impact growth.

- Parental anxiety - concerns about feeding and introducing new foods can limit dietary variety and expansion. This anxiety can lead to overly restrictive diets that fail to meet the nutritional needs of growing children.

- Ongoing inflammation

Quality of Life - Client and Family

A suspected or medically confirmed diagnosis of food allergy affects almost all aspects of family life. Parental anxiety regarding feeding and the introduction of new foods may negatively impact dietary expansion and variety. The role of the dietitian is crucial in managing these concerns, providing guidance to ensure nutritional adequacy and diversity, and alleviating parental anxiety.

The management of children with anaphylactic reactions to food requires a multidisciplinary approach involving several specialists and allied healthcare professionals to ensure comprehensive care. These professionals play critical roles in diagnosis, treatment, education, and support for both the child and their family.

TABLE 1.5 Roles and Responsibilities in Supporting Individuals with Food Allergies(9,25)

| ALLERGEN | Expanded Role and Responsibilities |

|

General Practitioner (GP) |

• Usually the first point of contact for children experiencing food-related allergic reactions. |

|

Specialist Dietitian |

• Collaborate with the medical team to support individualized patient management plans, ensuring dietary recommendations align with medical and allergist directives. |

|

Primary Care Practitioner: Pediatrician |

• Develop and implement a comprehensive, evidence-based screening protocol for all patients, especially those at higher risk for food allergies, such as infants. |

|

Immunologist/Allergist |

• Formulate and oversee personalized reintroduction protocols following an elimination diet, with a focus on gradual food challenges in a controlled environment to assess tolerance. |

|

Emergency Care Physician |

• Develop and distribute a comprehensive written food allergy action plan to patients and caregivers, including clear instructions on the use of rescue medications such as epinephrine auto-injectors, in the context of suspected IgE-mediated food allergies. |

|

School Health Team: Administrator |

• Establish and implement individualized action plans for students with food allergies, addressing both prevention and emergency management protocols. Given that a significant portion (25%) of food allergy emergencies requiring epinephrine (where there was no previous diagnosis) occur in schools, proactive measures are essential. |

|

Community Members: Little League Coaches |

• Cultivate a supportive and inclusive environment by acknowledging the presence of food allergies within the group |

|

Parent |

• Actively advocate for the child’s safety and well-being by ensuring all caregivers (e.g., teachers, babysitters, family members) are well-informed of the child’s food allergy action plan, with regular updates. |

|

Patient |

• Pursue a clear and confirmed diagnosis, seeking second opinions or specialist consultations when necessary, particularly when the initial diagnosis or management plan lacks clarity. |

| Psychologist |

• Supports the child and their families in coping with the psychological burden that often accompanies severe food allergies. |

Medical Nutrition Therapy (MNT)

Medical Nutrition Therapy (MNT) plays a crucial role in the medical care of individuals with suspected food allergies at two key stages: 1) during the diagnostic process and 2) in the management of food allergies. In the diagnostic phase of suspected mediated food allergies, MNT focuses on the strategic elimination of common food allergens from the individual's diet, followed by a systematic reintroduction of these foods (oral food challenge) to identify which allergens trigger adverse reactions and which are tolerated. This process helps establish a clear diagnosis while ensuring that nutritional needs are met during the period of dietary restriction.

Insert Practice Consideration

Aims of MNT after IgE Food Allergy Diagnosis

While the aims of MNT are tailored to each individual client/caregiver after the Nutrition Assessment and Nutrition Diagnosis, in general the types of aims for MNT for IgE food allergy medical diagnoses are below:

- To eliminate foods proven to cause an allergic reaction while maintaining a nutritionally adequate diet.

- To assist families in maintaining strict adherence to an allergen-free diet, while maintaining quality of life

- To improve nutritional intake, growth and development

- To prevent long-term complications

Overview of Medical Nutrition Therapy for IgE-mediated Food Allergies in Pediatrics

Once an IgE-mediated food allergy has been diagnosed by an allergist, the primary objective of MNT is to support the family in implementing dietary and behavioral modifications to prevent accidental exposure to the allergen. The focus of MNT shifts toward educating the patient, family members, and caregivers on allergen avoidance strategies, including the identification of allergenic ingredients on food labels, preventing cross-contamination during food preparation, and ensuring safe food choices outside the home.

Equally important is the education of all caregivers on the emergency management plan in the event of accidental allergen exposure. MNT ensures that caregivers are fully equipped to recognize the signs of an allergic reaction, understand the use of emergency medications such as epinephrine auto-injectors, and are prepared to take immediate action. This comprehensive education ensures that all individuals involved in the care of the child are informed and capable of managing both the dietary and medical aspects of food allergy management effectively.

In addition to allergen avoidance, MNT must ensure that the child's overall nutritional needs are met, particularly if a major food group, such as dairy or eggs, is eliminated. This may involve recommending appropriate nutritional alternatives or supplementation to prevent deficiencies in key nutrients such as calcium, vitamin D, or protein, thereby supporting normal growth and development despite the dietary restrictions.

The management of food allergies necessitates the involvement of family members and caregivers, especially in pediatric patients, who rely on others for meal preparation, food choices and safe dietary practices. The dietitian's role extends beyond addressing the individual patient to encompass a comprehensive evaluation of the surrounding family and social environment. This includes an assessment of the family's knowledge of food allergens, their proficiency in allergen-safe food preparation, their ability to access allergen-free foods, and the Psychosocial burden associated with managing the allergy. Importantly, the dietitian must assess the family's understanding of food allergies, including potential misconceptions. For instance, in some cases, caregivers may impose an unnecessarily restrictive diet which can lead to nutrient deficiency and poor health outcomes in the child.

A thorough knowledge assessment is essential for both the primary caregiver and the child, depending on the child's age and cognitive ability. This assessment encompasses understanding the nature of food allergy, the implementation of an emergency management plan, and specific knowledge regarding the identification and avoidance of allergen-containing foods. Since the impact of a child's food allergy extends beyond the individual to affect the entire family unit, it is critical to evaluate factors that influence family quality of life. This assessment allows the healthcare provider to develop strategies that not only manage the allergy but also help maintain or improve the family’s overall well-being.

Addressing topics that affect the family's quality of life, such as managing the emotional stress of food preparation, anxiety about accidental exposure, and the social limitations imposed by the allergy, is vital. By identifying these challenges, the dietitian can provide targeted education and support, empowering families to navigate the dietary changes required to avoid allergens while maintaining a balanced, nutritionally adequate diet and preserving the family’s quality of life.

In addition to allergen-specific considerations, the nutrition assessment for pediatric patients with food allergies must encompass all standard pediatric nutrition assessment parameters. This includes evaluating the adequacy of the child's overall nutritional intake to ensure it supports optimal growth and development. A critical component of this assessment is the estimation of energy and protein requirements, as well as the intake of nutrients necessary for growth, such as iron, calcium, protein, vitamin D, and essential fatty acids.

Particular attention is given to whether the child is achieving appropriate developmental milestones, which can be impacted by inadequate nutrition. For example, a child with a food allergy who is placed on a highly restrictive diet may be at risk for deficits in essential nutrients, leading to growth faltering or developmental delays. Anthropometric measurements, such as weight-for-age, height-for-age, and body mass index (BMI)-for-age, are essential tools to monitor growth trends and identify any deviations from expected growth patterns. These metrics, along with dietary intake assessments, provide a comprehensive picture of whether the child's nutritional intake is sufficient to support healthy physical and cognitive development.

For children with food allergies, there is an increasing awareness of the potential to develop maladaptive feeding behaviors from lingering associations with food and discomfort associated with eating. In some cases, the symptoms of feeding dysfunction may persist after the allergens have been removed from the diet and may require an assessment done by a pediatric feeding specialist. The importance of a multidisciplinary team of specialists (allergists, gastroenterologists, mental health professionals and feeding specialists) is key to successful intervention and treatment.

When selecting nutrition diagnoses, the dietitian's scope extends beyond the food allergy alone, taking into account the holistic well-being of the patient as well as the family and community environment in which the patient resides. This comprehensive approach aligns with the principles of patient-centered care, which recognizes that food allergies not only elicit a physiological response but also impose significant behavioral and psychosocial challenges that influence dietary intake and management strategies. Food allergies can provoke diverse psychological responses, including anxiety around eating, fear of accidental exposure and diminished QofL, both for the affected individual and their family. Thus, nutrition diagnoses from all three domains of Nutrition Diagnoses may be appropriate as follows:

- Intake domain, the identification of the intake of food allergen, or inadequate intake of essential nutrients due to elimination of foods containing the allergen

- Clinical domain, the identification of potential for changes in growth rate, or malnutrition,

- Behavioral-Environmental domain, the potential for limited knowledge or skills, beliefs and attitudes, impact on quality of life

The initial focus of nutrition intervention should prioritize equipping caregiver(s) with the necessary knowledge and skills to create an environment that minimizes the risk of accidental allergen exposure.

In this case (17), this entails acquiring knowledge about IgE-mediated peanut allergy, including the ability to identify allergen sources, and implement safe food preparation practices to prevent cross contamination. While knowledge is critical, it is equally important to provide counseling that facilitates the caregivers's integration of these practices into their broader lifestyle and community interactions.

The skill needed to plan a balanced allergen free diet that meets the nutritional requirements for normal growth and development is a key topic. Depending on the specific allergen, the impact on meal planning to include alternate sources of missing nutrients varies. The meal plans are based on the previously identified energy levels needed for optimal growth and development.

Creating a safe home environment depends on the ability to read and select only allergen free food products. Every country has food labeling guidelines, but generally the labeling for packaged foods addresses the how to include the list of ingredients as well as precautionary labeling to identify food products that are NOT guaranteed to be allergen free despite not including the allergen in the list of ingredients.

In addition to creating a safe home environment, there are specific strategies needed to ensure a safe allergy-free environment outside the home. The types of environments addressed depend on the age and lifestyle of the client with the food allergy.

The topics addressed for minimizing risk of accidental exposure vary depending on the age of the individual with the allergy. For children of school age, special attention is directed toward daycare and school environments.

Specifically for IGE mediated allergies, the caregivers, individual and family members must be have advanced knowledge and confidence in their skill necessary to implement the emergency care plan, administer the epi-pen and recognize the varying signs and symptoms of mild and severe allergic reactions.

Since the food allergy treatment strategies and products are continually evolving, it is also important to help patients/caregivers develop skills to interpret media blogs, advertisements, or internet sources of "information".

Nutrition Monitoring and Evaluation(28)

Since a major focus in the nutrition intervention is ensuring the caregiver has sufficient knowledge and skills to implement a diet that is allergen free and also nutritionally adequate, assessing knowledge and skills at the end of the consultation and again during follow-up sessions is important. The level of knowledge about various topics may vary. Specifically, for IgE mediated allergies where anaphylaxis is possible, advanced knowledge of the Food Allergy Emergency Care Plan as well as the knowledge and skill necessary to implement an allergen free diet.

References — Food Allergy

ASCIA_HP_Checklist_Anaphylaxis_Adrenaline_Prescribers_2021.pdf

27. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Nutrition Terminology Reference Manual (eNCPT): Dietetics Language for Nutrition Care. NCP Step 3: Nutrition Intervention. 2020. [Internet]. [cited 25 Septemeber 2024]. Available from: https://www.ncpro.org/pubs/2020-encpt-en/page-055

28. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Nutrition Terminology Reference Manual (eNCPT): Dietetics Language for Nutrition Care. NCP Step 4: Monitoring and Evaluation. 2020. [Internet]. [cited 25 Septemeber 2024]. Available from: https://www.ncpro.org/pubs/2020-encpt-en/page-015a

1. Adapted from National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Finding a path to safety in food allergy: Assessment of the Global burden, causes, prevention, management, and public policy. Washington DC, National Academies Press; 2017

2. Haas AM. Feeding disorders in food allergic children. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2010 Jul;10(4):258-64. doi: 10.1007/s11882-010-0111-5. PMID: 20425004.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)